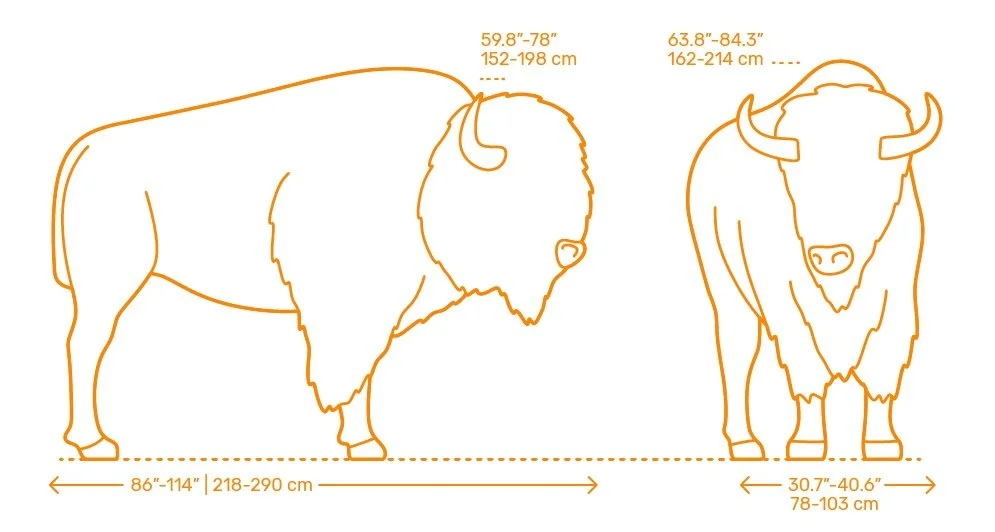

Size:

Bison are North America’s largest extant land mammal, and the national mammal of the United States. Bull bison typically weigh 2,000 and 2,200 pounds. with cows topping out around 1,600 pounds. They stand between 5 and 6 feet at the shoulder and present an imposing presence when encountered, especially on foot. Despite this incredible size, they are as fast as a racehorse.

Diet:

Bison are simple-minded creatures with an incredible amount of knowledge. They eat grass, grass, and only grass. But by the wonders of evolution, they cultivate their own greenery. Bison clip the grass and move across the landscape in such a way as to increase the biomass of the grass they graze in a way that wouldn’t happen without them.

Mating:

The rut occurs in August,

The primary cause of the buffalo’s extermination, and the one which embraced all others, was the descent of civilization, with all its elements of destructiveness, upon the whole of the country inhabited by that animal. From Canada to Mexico, the home of the buffalo was everywhere overrun by the man with a gun, and, as has ever been the case, the wild creatures were gradually swept away, the largest and most conspicuous forms being the first to go. The secondary causes of the extermination of the buffalo may be catalogued as follows:

1. Man’s reckless greed, his wanton destructiveness, and improvidence in not husbanding such resources as come to him from the hand of nature, ready made.

2. The total and utterly inexcusable absence of protective measures and agencies on the part of the National Government and of the Western States and Territories.

3. The fatal preference on the part of hunters generally, both white and native, for the robe and flesh of the cow over that furnished by the bull.

4. The phenomenal naivety of the animals themselves, and their indifference to man.

5. The perfection of modern breech-loading rifles and other firearms in general.

6. The government policy of controlling native peoples by US General John Schofield, but it “killing off the savages’ food source until there is no more indian frontier in this great country”.

The slaughter of the American bison west of the Mississippi followed the tracks of the railroads like a shadow. At first, the animals were killed to feed the armies of men laying steel across the prairies. Later, when the lines were complete, the trains themselves became moving hunting blinds. Tourists riding west were handed rifles and encouraged to lean out the windows and fire at the herds for sport. The bison, which had roamed for millennia without predators on that scale, fell in droves.

The rails didn’t just bring hunters. They fractured the land itself. Where once the bison moved freely across endless grass, now the tracks split their range into pieces. It was said you could travel fifty miles out from the tracks and not see a single animal. With herds divided and weakened, the hide and tongue trade surged. A salted bison tongue might fetch a dollar on the market, a small fortune in 1870s money, and the robes made from their thick winter coats fueled a booming industry.

The prairies soon filled with bones, the remnants of millions of slaughtered animals left to rot. “Bone pickers” combed the plains, gathering skulls and skeletons for fertilizer or industrial use. Some hunters killed bison only to return a year later for the bones. Others shot them simply because they were there. The endless procession of death became so normal that it’s said the bleached piles of bones sometimes towered taller than a man.

By the 1880s, the killing had taken on another purpose. The U.S. government encouraged the destruction of herds to undercut the livelihood of Native nations. If the bison were gone, the tribes who depended on them would have little choice but to accept rations and dependency. It was not just ecological devastation; it was policy, calculated and cruel.

By 1890, the once-immense herds that had thundered across the plains were reduced to phantoms. Ranchers occasionally spotted twos and threes at the ragged edges of settlement, but they were no longer a functional population. From tens of millions, the American bison had fallen to mere dozens, ghosts scattered across a continent that had once belonged to them.

Bison intolerance largely stems from fear and longstanding tradition rather than solely factual reasoning. It is true that when bison come into contact with ranching operations, they can cause issues such as fence damage and competition with cattle for grazing resources. However, these challenges are generally manageable with proper practices.

The primary concern fueling intolerance is disease transmission, specifically regarding Brucella abortus. This pathogen causes permanent infertility in cows, presenting a serious threat to livestock productivity. Ironically, brucellosis was originally introduced into bison populations from European domestic cattle, which played a role in the bison’s historical decline. Today, bison serve as a reservoir for the disease.

An intensive vaccination campaign successfully eradicated brucellosis in domestic cattle by 2008, but since cattle are no longer routinely vaccinated, there is apprehension about the possibility of bison re-transmitting the disease back to cattle populations. It’s worth noting that elk also carry and transmit brucellosis to cattle at a significantly higher rate, yet they do not face the same level of scrutiny or intolerance as bison.

Understanding these nuances can help shift perspectives towards more balanced wildlife management that addresses risks while recognizing the ecological and cultural importance of bison.

Bison “Recovery” in Yellowstone

The extermination of bison throughout the West in the 1800s nearly eliminated them from Yellowstone. Even after the park was established in 1872, poachers faced few deterrents. With only 25 bison counted in the park in 1901, Congress appropriated $15,000 to augment the herd by purchasing 21 bison from private owners. As part of the first effort to preserve a wild species through intensive management, these bison were fed and bred in Lamar Valley at what became known as the Lamar Buffalo Ranch.

As the herd grew in size, bison were released to breed with the park’s free-roaming population. Bison from the ranch were also used to start and supplement herds on other public and tribal land. Today, the Yellowstone bison population numbers in the thousands. It’s one of the largest populations in North America and among the most genetically pure because the has been exceptionally little outbreeding with cattle.

A program to raise bison like domestic cattle in Yellowstone may seem incongruous and unnecessary in retrospect, but the buffalo ranch stands as a reminder that today’s well-intended wildlife management policies may have unintended consequences and be overturned by changing values and advances in ecological knowledge.

Today, the herd numbers around 5,000. This represents the largest wild, free-ranging bison herd in over 150 years. Yellowstone National Park, with help from tribal partners, is an exporter of bison to wild spaces throughout the country. Areas adjacent to the park have even restored some tribal “hunting”, although it borders on the unpallateable. While bison inside Yellowstone National Park are granted a suite of protections, bison that leave the park can face major hurdles. These include lawsuits to lower the total number of bison in Yellowstone and threats to remove bison tolerance zones adjacent to the park. This would effectively mean that any bison caught outside of park boundaries would be shot by government hunters.